Last week the Wall Street Journal published an article on the threat of farmers to Cargill and ADM. In many ways this is laughable. These grain merchants scale so far out weighs their customers (the farmers) that there is no foreseeable future in which they will come under threat. This kind of scale is salivated over in boardrooms across the country. Row crop agriculture is in many ways the addressable market ($189,139,447,000 in revenue in 2016) for new companies to attempt to disrupt. However, as has been discussed here before, the market penetration eludes most. Ultimately, rapid, nation-wide scale should not be a primary objective of any row crop agriculture business.*

First, let’s justify the laughable comment above. Archer Daniels Midland handled 22.7 million metric tons of corn and 34.7 million metric tons of oilseeds. So, that is about 894 million bushels of corn and 638 million bushels of soybeans (if half of the oilseeds are soybeans).

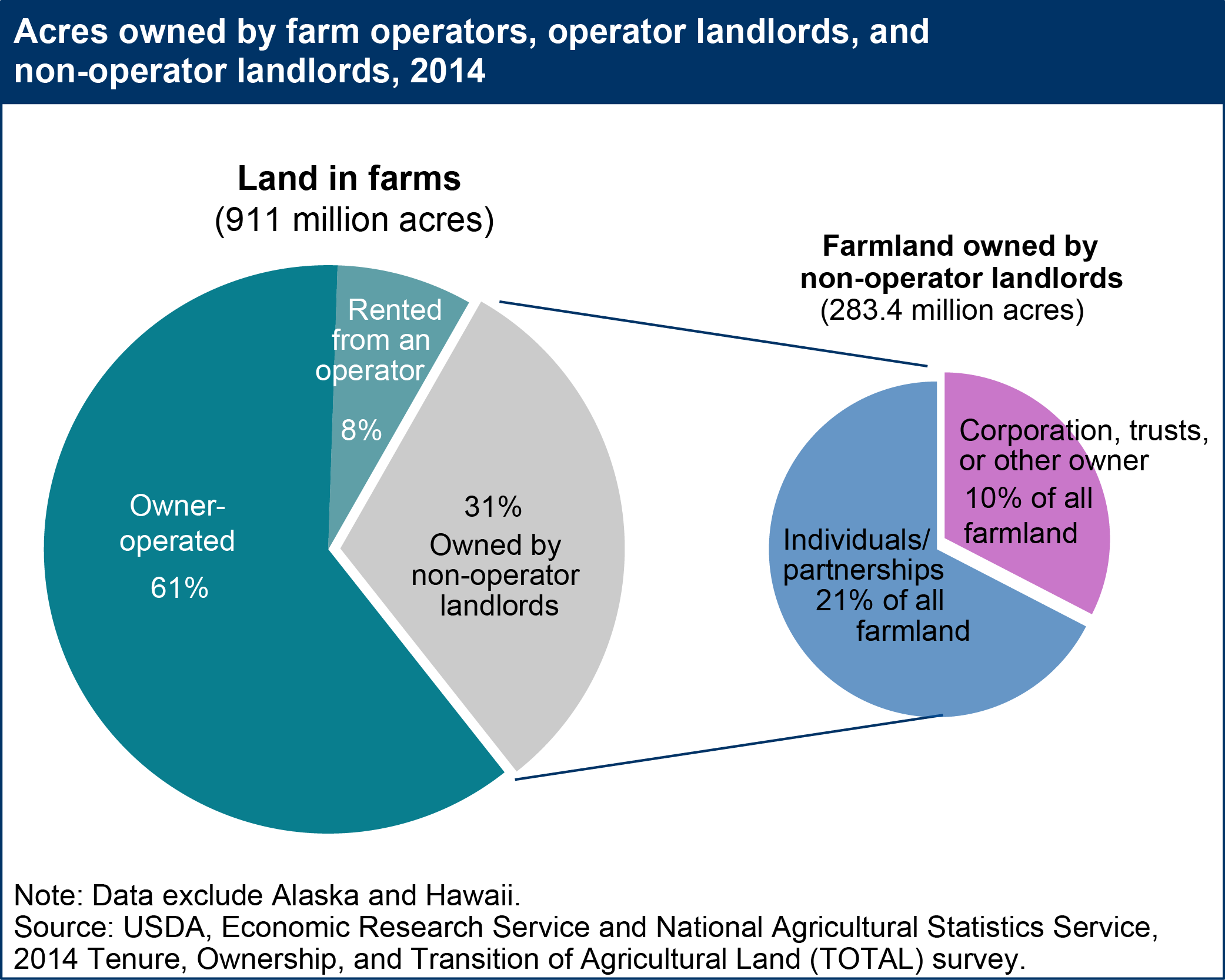

Now let’s look at production. A decent guess at total row crop acres in the United States would be 400 million. The largest grower of commodity crops in the United States is 200,000 acres. There are a few others who are around 100,000 acres. For argument’s sake let’s assume the top growers amount to 1,000,000 acres. If these growers produce 50% corn and 50% soybeans at the national average of 178.4 bushels of corn and 51.6 bushels of soybeans, then they produce 89 million bushels of corn total and 25.8 million bushels of soybeans total. This is 9% and 4% of ADM’s handled bushels per year. When you think that ADM shares the market with Bunge, Cargill, Consolidated Grain and Barge, and many other co-ops and direct delivery points like feed mills, their shared production is a minuscule number. By acreage these producers are 0.25% of the total in the US. There is effectively no large scale bargaining power for any producer against grain merchants.

Farmer Scale

So, if farmers do not pose a substantial threat to any grain merchant, then why does the WSJ article matter. Well, farmers can have a local advantage at any given elevator. Each elevator has to have a certain amount of grain flow through it to justify the expense of its existence in a certain area. In other words, the merchants have to cover their costs of operating in an area and large farmers are a way to take large chunks of that total grain flow. Therefore, they get a premium for their large quantities. However, this is a small amount of the total profits they are taking from any elevator. It is hard to even imagine the elevators consider these growers to be “loss leaders.”

However, the better question the article raises is, “does this matter for farmers?” In short, yes. Scale matters for farmers for many reasons. A local advantage with an elevator can mean better pricing for the producer and better margins for him than for his neighbors (aka competitors). He can justify higher rents than others around him, although higher rents should obviously be relative to his costs. Scale helps him here too though. With larger scale he can often bargain for better deals with inputs vendors and even with equipment dealers. Not only are his costs lower on acquiring equipment, but he can often have fewer pieces of equipment per acre. If a farmer needs 2.5 tractors per 5,000 acres, then someone with 10,000 can have 5 tractors while a 5,000 acre farmer may be forced to have 3. Not only does he require fewer pieces of equipment but also he is hurt less with any individual equipment problem. If one of the 3 tractors goes down, farmer 1 loses 33% of his capacity. If farmer 2 has a tractor go down, he loses 20%. This may seem fairly straightforward; however, the implications during peak periods of work are massive. This advantage compounds with size.

With this size advantage comes a higher fixed cost, though. Just for the additional 2.5 tractors farmer 2 has $1,000,00 of additional equipment on his balance sheet. Add on the other costs of operating at double the size of farmer 1 and the numbers escalate quickly. This growth cannot be had overnight.

Row crop agriculture requires lots of expensive assets, and any asset heavy business is difficult to scale. This is the first and most undervalued problem with high growth farming businesses. The problem is not unrecognized, however. Many new entrants hope to remain asset light, aggregate customers, create demand and profits in order to “share” with their customers. Much like Amazon is the perpetual low price machine these companies want to be the perpetual profit machine.

Landowner Scale

For landowners scale matters, but not as directly as with farmers. A landowner with a couple hundred acres can only rent to one farmer. She has severe concentration risk with her tenant and with her weather risk. A tenant could default mid year or a bad storm could knock out a crop. With greater acreage a landowner can rent to multiple tenants, have multiple crops on her land, or even own land in different locations that have completely different climate. When this landowner invests in a fund she diversifies herself even more. For institutional landowners paperwork, land improvements and tenant management can be handled internally allowing for greater oversight and improvement of the properties and likely greater returns. Many of these companies are at a national scale, but they have also been around for decades and have growth their assets slowly. However, as was mentioned in Land Values Justified, even these multi-billion dollar companies have a small footprint when viewed from the national scale.

Seeking Scale

The true masters of scale are the merchants, the equipment manufacturers and the inputs vendors. These companies have built infrastructure, sales pipelines, and supply chains that span the US. This is the scale that matters. It is what allows them to reach a massive customer base and provide high levels of service throughout the country.** Almost every new company in agriculture has tried to either recreate or tap into these pre-existing structures. For small companies tapping into an equipment dealer network or a vendor network can allow for much greater market penetration than would otherwise be possible. Large companies trying to create their own distribution are effectively trying to create the proverbial plane as it goes down the runway – not a promising venture when dealing with real world logistics and large volume products.

Why is this being done?

It is worth taking a minute to discuss the ideas prevalent among the silicon valley set. Often, brilliant people with hoards of money come into an industry in order to disrupt it, knowing little, but armed with a deep knowledge of the way things should work and do work in other industries make deep, influential change. Many even create a new subsection of an industry with new technology and ways of operating. Books like Zero to One chronicle these people and their tenacity. These changes can be impressive and life altering for many people’s everyday life.

Mike Maples in an interview with Tim Ferriss (transcript) gives an incredible metaphor on how he understands these companies and the change they bring about.

But like, I like the metaphor of surfing because you can be a skilled surfer. But you don’t really control surfing. Right? You can sort of control the board-ish, even if you’re good, you can only barely control it. But you can’t control the wave. I look at … To me the magic that animates the technology industry is a combination of Moore’s Law and Metcalf’s Law. I think we all benefit from the magic of Moore’s Law and Metcalf’s Law. It’s like, literally as powerful as the ocean waves below you when you surf. I look at it like the job of a start up founder is to surf a valid wave. The wave is usually bigger than the company. Right?…

We believe that those gathering waves are more powerful than any one company. The job of the tech entrepreneur is to leverage the awesome, massive power of all of the fury of the ocean beneath him of Moore’s Law and Metcalf’s Law. Just surf into the beach. Give Moore’s Law enough time, it will breach the advantage of any incumbent. Give Metcalf’s Law enough time, and it will create an insurmountable mode…. To me, the tech industry is magical. There’s been tulips in the past. There’s been the crash of 29. There’s been the real estate bubble. There’s bubbles all the time. There’s manias all the time. But tech is animated by two valid exponential forces that are super powerful. They are the asymmetric attack vector of the entrepreneur. They are the rock in David’s slingshot. I look for founders who have some type of fundamental contrarian insight about where a wave is about to gather. Then, hopefully they have the stuff to surf it. If they do, I’m like “Hey let’s rock. Unconditional love. Let’s go.”

Metcalf’s Law in this case simply means that the value of a network increases exponentially with each additional user. Moore’s Law, simplified, means that computing power doubles about every two years. So, when a network is created on top of computing power there is a double effect of growth – the ultimate tailwind or, in this case, wave.

The problem in agriculture is these two laws do not have the same foundation on which to build as they do in other industries. They have not had enough time to create the insurmountable mode.

While Moore’s law allows computers to attack complex problems and make connections at a faster rate, it depends upon the base layer of data in order to begin its computation. For a company like Facebook, where massive amounts of data are being uploaded daily, there can be impressive results in ability to understand its users in short order. Further, each user uploads or views a certain amount of items each time he or she logs in. The user is a clear and definite point to which Facebook can trace its data and profile that point against similar points. On a row crop farm there are far more variables and far fewer unique points to which the data can be traced. This is, again, simplified as data can be layered, smoothed and allocated over areas to make broader conclusions. However, what can not be simplified is the end result. In most cases the end result for which these companies get paid is yield. Yield data is poor at best. The harvesters give relative data about what has been harvested, but it is rarely linked back to any absolute data about how much crop has been delivered off any field much less point within a field. Without good production data in season data collection is rarely actionable. Other information like number of land sales, price of sale for land, or even quantity and type of inputs used are scarce throughout row crop agriculture. Without this information the computing power must start much farther back the exponential curve of its usefulness.

Metcalf’s law suffers from an altogether different problem with the same result. Farms are not connected. There are no widely used technologies which connect the businesses of farms. Most payments are made with a checkbook and credit account. So, the problem of getting them connected to something much more complex like an ERP (enterprise resource planning) system is a tall order. It is as if you had to teach someone to use a computer before they could use Facebook. This should not be seen as the farmer’s fault either. There have been few incremental improvements in new technology which have made the farmer’s life easier on which new technology can build. Again, the industry is much further up the curve than other industries; it is not ready for widespread use of systems and connectivity. To borrow from Maple’s analogy the wave is just starting to form; it cannot be surfed…yet.

Things will change. These laws will have an incredible effect on the industry, but these are early days. We are ending the opening and beginning the middle game of technology in agriculture.

If the power laws of technology won’t help the yield, what about making connections between people for services? Uber for X… grain delivery, combines, tractors, labor, parts delivery. This gets much closer to a tractable problem. However, here we run into the problem of scale again. There is a supply problem. Andrew Chen recently wrote about this problem on his website.

Rideshare is special. Acquiring a broad base of labor for driving is expensive, often $300+. But then they can get requests all day. You can work 20 hours and even 50 hours a week if you want. You continually need the driver app to find new customers

Where a lot of “Uber for x” companies fall down – valet parking, car washing, massages, etc – is that demand is often infrequent and there’s spikes at a few points in the day. What’s your supply side supposed to do the rest of the time?

In other words, “Uber for x” cos often have the same cost of acquisition and cost of labor as rideshare, but can’t fill their time with work as smoothly / profitably.

Uber for planting, harvesting and even grain trucking all fall into this category. There are spikes in need and they frequently occur at the same time nation wide. Even when the timing is different, the marketplace companies would have to convince massive amounts of individuals to move across the country in order to handle the supply need. There are individuals who do this now, but not in the quantities needed to justify a two sided marketplace for the service.

Where does scale work?

Massive scale works for companies without a product or service that has to be distributed physically. These products generally break up something complex or expensive. For instance, a Vanguard for grain sales could scale nationally. This product could be marketed to producers to give them the annual average grain price for their crops. This reduces marketing risk and allows farmers to focus on what they do best – grow as much crop as inexpensively as possible. This product would leave the basis open for growers to market, but that may be a tractable problem the company could solve down the road as well. There could be other financial instruments for borrowing money for land or for operating loans. New financial products can scale quickly and will be necessary as farmers outgrow their traditional forms of financing.

Scale for the rest of us

For most companies though the best option is to establish regional scale. Create a network of growers who use a product or service and extend from a solid base of users.

This is the crux of the problem with a nationally focused company, though. It needs to gain traction in one area in order to expand into another. However, in many cases, like that of Uber for X, supply is constrained within a region.

Therefore, for a company to succeed it must be have products and services which can be sold within a region. It must build reputation, assets, distribution, and employee skills and knowledge before venturing out into other regions. Reputation matters in agriculture and rapid change is uncommon. Growth in a sustainable way is key. Below is a little inspiration. It’s a heat map of Walmart’s growth over time. This is what growth should look like.

Uber (the original one) did this at first by concentrating on high population density cities and bridging out from there. However, with many products having just one sales cycle per year the growth can be slow. Any service which is not linked to the growing season will have better luck with its growth trajectory. However, there are simple services which could be offered and are needed. Parts delivery – have on-demand couriers who deliver parts to a field where work is being done. This would literally cut the time of delivery in half as someone would not have to go out to the store and come back. The courier pick up the part and deliver it from the store instead. Labor training – there are companies who train computer programmers and take a portion of their first few year’s salaries as payment. This could be done for high end farm jobs like planting or harvesting, which are more technical and for which good labor is hard to find. There are many problems to be solved.

Ultimately farming is not yet a business to which rapid scale lends itself. There are opportunities to grow a company at an impressive rate, but not by Silicon Valley standards. As Maple’s waves build opportunities the speed of change will accelerate. However, as he points out you have to give it enough time.

*For argument’s sake let’s say this means any business with under 15 years operating experience and more than $5,000,000 in assets.

** Despite a few justified complaints, a farmer can order seed and chemical have it delivered the same day. There are technicians who show up to fix tractor problems on a regular basis. There are many things which could be improved, but the system as it stands is impressive. This is true especially considering the large swaths of area this is done over.